一个不为人知的Amgen故事:富含GC基因表达技术的发现

独家抢先看

文/惠觅宙

今天我想与大家分享一个鲜为人知的Amgen故事。Amgen(下图)成立于1983年,是全球最大的生物技术公司,现在年销售额超过400亿美元。在20世纪80至90年代期间,它是《财富》全球500强企业之一,并创造了当时全球股票增长率第一的奇迹。

我于1997年加入Amgen。当时我是跟随前妻一起加入了红细胞生成素(EPO)发明人林富坤博士的研究团队。

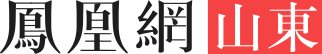

在此之前,我在多伦多大学附属的Mount Sinai医院从事博士后研究,跟随Andras Nagy博士工作。Nagy博士(下图)是转基因小鼠领域的领军人物,他编写的那本“小黄书”《Transgenic Mice》(《转基因小鼠》)被认为是该领域的“圣经”。他还建立了最早用于制造转基因小鼠的胚胎干细胞系—R6细胞系。

在我前往Amgen之前,Nagy博士让我研究一个名为CAG的基因表达质粒。这个CAG启动子的基因表达强度极为惊人。日本科学家后来将CAG序列与绿色荧光蛋白(GFP)结合,创造出了著名的绿色转基因小鼠(见下图)。

CAG启动子主要采用改造后的鸡或鸟类β-肌动蛋白(beta-actin)基因启动子,这是一个“看家基因”(housekeeping gene),GC含量极高——超过75%。CAG质粒的GC含量高达74–90%,因此无论是进行PCR还是DNA连接实验都极其困难。当时我已经是一名技术娴熟的分子生物学家,但在操作这个构建体时仍然异常艰难——PCR无法扩增,连接不成功,酶切不彻底,表达还常常丢失。

后来我发现,这个CAG启动子具有异常强大的基因表达能力,使Amgen能够成功表达许多以往难以生产的重组蛋白。

最终,我了解到CAG启动子的前身实际上源自Amgen自己的基因表达质粒。早在我加入Amgen十多年前的上世纪80年代,Amgen的一个实验室就已经开始使用这种改造过的鸡(鸟类)β-肌动蛋白基因启动子,也就是后来CAG的雏形。

在Amgen期间,我经常看到一位年老、消瘦、驼背、行动不便的老人。他是Amgen的早期合作伙伴之一,为Amgen的红细胞生成素表达与生产作出了重大贡献。他的名字叫Norman Davidson(下图),是加州理工学院(Caltech)著名的分子生物学家。美国总统比尔·克林顿曾亲自授予他国家科学奖章(National Medal of Science)。

他的博士生Nevis Fregien非常有耐心和技术天赋—他成功克隆、剪切并连接了一个GC含量极高、约1kb大小的鸡β-肌动蛋白基因启动子片段。这个“看家基因”的GC含量高达75.3–90.8%,使PCR扩增和DNA连接极为困难。Fregien应当是一位非常出色的博士生。

有一次,我偶然在Amgen内部资料中发现了一份加州理工学院(Norman Davidson实验室)与Amgen之间金额为10万美元的合同。合同内容允许Amgen使用这种改造后的鸡β-肌动蛋白启动子来表达红细胞生成素(EPOGEN)(下图)。后来的一系列研究(文献1–6)表明,这种鸡β-肌动蛋白启动子可能源自史前大型动物恐龙的细胞骨架基因(即β-肌动蛋白基因)启动子,因此具有异常强大的表达能力。

Amgen因其红细胞生成素而闻名于世,而该基因正是由我前妻的导师林富坤博士克隆的。事实上,就在Amgen濒临资金耗尽、面临解散的前一个月,林博士仍坚守实验室(下图),冒着放射性危害进行实验,最终成功克隆出红细胞生成素基因,缔造了生物科技史上最传奇的成功故事之一。

红细胞生成素基因克隆完成后发现,其翻译后的蛋白具有五个糖基化位点,只能在动物细胞中表达和生产。在20世纪80年代末期,尚未出现强大的哺乳动物细胞表达系统,当时常用的SV40和CMV启动子表达量不足3 mg/L。然而,Amgen的EPO表达水平却高达36 mg/L(在低密度转瓶培养的CHO细胞中)。由于EPOGEN每次注射剂量仅为300微克,这样的表达水平完全满足当时的工业化生产与销售需求。

根据这份加州理工与Amgen签署的10万美元合同、Norman Davidson教授当时在Amgen工作的事实,以及转瓶培养CHO细胞能达到36 mg/L的高表达水平,我认为Amgen的红细胞生成素(EPOGEN)实际上是使用了来自Norman Davidson教授实验室改造的鸡β-肌动蛋白启动子。

在1990年代,转瓶培养的细胞密度远低于现代生物反应器的悬浮培养(下图),因此当时的高表达量更显得非同寻常。Amgen能成功商业化EPOGEN,是一次幸运又偶然的成功,而加州理工在其中的贡献不可忽视。

后来,我使用进一步改造的鸡β-肌动蛋白启动子进行表达研究,发现其在CHO细胞中可驱动含有五个糖基化位点的红细胞生成素和透明质酸酶PH20的表达,表达量同样可达36 mg/L以上。换句话说,改造的鸡β-肌动蛋白启动子对有多个糖基化位点的蛋白的表达非常有用。

Amgen官方宣称EPOGEN是利用源自哥伦比亚大学的CHO-DHFR细胞系和pDSα2 DHFR基因生产的。但我认为,Amgen很可能将基于鸡β-肌动蛋白启动子的表达质粒作为商业机密予以隐藏。我在Amgen工作多年,从未成功操作过pDSα2 DHFR微基因,因此我对这一官方说法表示怀疑。注:当时CHO-GS表达系统尚未出现。

Amgen当年将其细胞库样品存放在美国典型培养物保藏中心(ATCC)。如今只需使用现代PCR技术即可确认当时是否使用了富含GC的鸡β-肌动蛋白启动子。如今距离那时已过去40多年,法律追溯也已无从谈起。

基于鸡β-肌动蛋白启动子的质粒具有极其强大的表达能力。2010年,我在《中国科学》(中英文版)上发表了相关研究成果(文献1,下图)。我提出鸡与恐龙具有同源起源(文献1–6),并认为这种鸡β-肌动蛋白启动子可能是恐龙强大细胞骨架基因系统的遗传残迹,在进化为鸟类后其功能被埋藏、失去了异常强大的表达活性。

有趣的是,中国的新冠腺病毒疫苗所采用的基因启动子,也是来源于这种改造后的鸡β-肌动蛋白启动子。我进一步认为,富含GC的DNA片段与DNA甲基化及转录因子结合密切相关。我一直坚信,对富含GC基因表达技术的深入研究与应用,终有一天将会成为诺贝尔奖级别的科学发现。

参考文献

1、Jia Q, Wu H, Zhou X, Gao J, Zhao W, Aziz J, Wei J, Hou L, Wu S, Zhang Y, Dong X, Huang Y, Jin W, Zhu H, Zhao X, Huang C, Xing L, Li L, Ma J, Liu X, Tao R, Ye S, Song Y, Song L, Chen G, Du C, Zhang X, Li B, Wang Y, Yang W, Rishton G, Teng Y, Leng G, Li L, Liu W, Cheng L, Liang Q, Li Z, Zhang X, Zuo Y, Chen W, Li H, Hui MM. A "GC-rich" method for mammalian gene expression: a dominant role of non-coding DNA GC content in regulation of mammalian gene expression. Sci China Life Sci. 2010 Jan;53(1):94-100. doi: 10.1007/s11427-010-0003-x. Epub 2010 Feb 12. PMID: 20596960.

2、Nevis Fregien, ,Norman Davidson. Activating elements in the promoter region of the chicken β-actin gene, Gene, Volume 48, Issue 1,1986,Pages 1-11,ISSN 0378-1119,

https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1119(86)90346-X.

(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/037811198690346X)

3、Kost T A, Theodorakis N, Hughes S H. The nucleotide sequence of the chick cytoplasmic beta-actin gene. Nucleic Acids Res, 1983, 11: 8287—8301

4、Vinogradov A E. DNA helix: the importance of being GC-rich. Nucleic Acids Res, 2003, 31: 1838—1844

5、Cyranoski D. Giant bird-like dinosaur found: Chinese researchers unearth a surpising find. Nature, published online, 2007, 13 2 Fucheng Z H, Zhonhe Z H, Xing X, et al.

6、A bizarre Jurrassic maniraptoran from China with elongate ribbon-like feathers. Nature, 2008, 455: 1105—1108

An Untold Story of Amgen: The Discovery of GC-Rich Gene Expression Technology

By Mizhou Hui

Today I would like to share with you an untold story about Amgen . Amgen (pictured below), founded in 1983, is the world’s largest biotechnology company, with annual sales exceeding 40 billion USD now. During the 1980s and 1990s, it was among the Fortune Global 500 and achieved the highest stock growth worldwide.

I joined Amgen in 1997. At that time, I went there with my former wife, who joined the research team of Dr. Fu-Kuen Lin (pictured below), the inventor of erythropoietin (EPO).

Before that, I was conducting postdoctoral research at Mount Sinai Hospital of the University of Toronto, working with Dr. Andras Nagy. Dr. Nagy (pictured below) is a leading figure in the field of transgenic mice and the author of the “small yellow book” Transgenic Mice, considered the “bible” of this field. He also established the first embryonic stem cell line used for generating transgenic mice, known as R6.

Before I went to Amgen, Dr. Nagy had me work on a gene expression plasmid called CAG. The CAG promoter had astonishing gene expression strength. Japanese scientists later combined this CAG sequence with green fluorescent protein (GFP) to create the famous green transgenic mouse (pictured below) .

The CAG promoter mainly uses a modified version of the chicken or avian beta-actin gene promoter, which is a “housekeeping” gene with an extremely high GC content—over 75%. The GC content of the CAG plasmid is so high (74–90%) that performing PCR or DNA ligation with it is extremely difficult. At the time, I was a skilled molecular biologist, yet working with this construct was truly challenging. PCRs would fail, ligations wouldn’t work, restriction digestion was messy, and gene expression was often unstable or lost.

Later, I discovered that this CAG promoter possessed extraordinarily strong expression ability, allowing Amgen to express many recombinant proteins that were otherwise difficult to produce.

Eventually, I learned that the CAG promoter’s predecessor actually originated from Amgen’s own gene expression plasmid. Over ten years before I joined Amgen—in the 1980s—one of Amgen’s labs had already begun using a modified version of the chicken (avian) beta-actin promoter, the same one later known as CAG.

At Amgen, I often saw an elderly, thin man with a curved spine who walked with difficulty. He was one of Amgen’s early collaborators and made major contributions to the expression and production of erythropoietin. His name was Norman Davidson(pictured below) , a distinguished molecular biologist from Caltech (California Institute of Technology). President Bill Clinton personally awarded him the National Medal of Science.

One of his PhD students, Nevis Fregien, showed remarkable patience and skill—he managed to clone, cut, and ligate a GC-rich, 1 kb-long chicken beta-actin promoter fragment. This “housekeeping” gene promoter has an astonishing GC content of 75.3–90.8%, making PCR amplification or ligation extremely challenging. Nevis Fregien must have been an exceptionally talented PhD student.

By chance, I found an internal Amgen document showing a $100,000 contract between Caltech (Norman Davidson’s lab) and Amgen, allowing Amgen to use this modified chicken beta-actin promoter for expressing erythropoietin (EPOGEN) (pictured below) . Subsequent studies (Refs. 1–6) indicated that this chicken beta-actin promoter might have originated from the beta-actin promoter of large ancient animals such as dinosaurs, which may explain its extraordinarily strong expression power.

Amgen became world-famous for its erythropoietin, cloned by my former wife’s supervisor, Dr. Fu-Kuen Lin(pictured below) . In fact, just one month before Amgen was about to run out of funds and dissolve, Dr. Lin insisted on staying in the lab and working with hazardous radioactive materials—finally succeeding in cloning the EPO gene and creating one of the most legendary success stories in biotech history.

The EPO gene, once cloned, contained five glycosylation sites and could only be expressed and produced in animal cells. In the late 1980s, before modern mammalian expression systems were developed, typical promoters like SV40 and CMV could yield less than 3 mg/L of recombinant protein. However, Amgen’s EPO expression level was extraordinary—36 mg/L in CHO cells cultured in low-density roller bottles. Since each therapeutic dose of EPOGEN was only 300 µg, this yield was more than sufficient for large-scale production and commercialization.

Based on the $100,000 Caltech–Amgen contract, the presence of Professor Norman Davidson at Amgen, and the unusually high expression level (36 mg/L) achieved in roller bottle CHO cell cultures, I believe that Amgen’s erythropoietin (EPOGEN) was in fact expressed using the modified chicken beta-actin promoter from the Davidson lab.

In the 1990s, roller-bottle cell culture (pictured below) had much lower cell density than modern bioreactor suspension cultures, which makes the high yield even more impressive. Amgen’s commercial success with EPOGEN was therefore both fortunate and serendipitous, and Caltech’s contribution was crucial.

Later, I conducted studies using further-modified versions of the chicken beta-actin promoter and found that it could drive expression of both EPO and hyaluronidase PH20 at levels above 36 mg/L in CHO cells.

Amgen officially claimed that EPOGEN was produced using a CHO-DHFR cell line and a pDSα2 DHFR minigene obtained from Columbia University. In my opinion, Amgen likely kept its chicken beta-actin promoter-based plasmid as a trade secret. During my years at Amgen, I never successfully worked with the pDSα2 DHFR minigene and personally doubt the official claim. (Note: at that time, the CHO-GS expression system did not yet exist.)

Amgen deposited its cell bank samples at the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Modern PCR techniques could easily confirm whether the GC-rich chicken beta-actin promoter was indeed used. More than 40 years have passed—legal concerns no longer apply.

The plasmid based on the chicken beta-actin promoter is exceptionally powerful. In 2010, I published my findings about it in Science in China (both English and Chinese editions) (Ref. 1)(pictured below) . I proposed that chickens and dinosaurs share a homologous origin (Refs. 1–6), and that the chicken beta-actin promoter might be a genetic remnant from dinosaurs’ strong cytoskeletal gene system, which later became silenced in birds.

Interestingly, the gene promoter used in China’s COVID-19 adenovirus vaccine is also derived from this modified chicken beta-actin promoter. I further believe that GC-rich DNA fragments are closely linked to DNA methylation and transcription factor binding. I have long envisioned that the exploration and application of GC-rich gene expression technology will one day be recognized as Nobel Prize-worthy work.

References

1、Jia Q, Wu H, Zhou X, Gao J, Zhao W, Aziz J, Wei J, Hou L, Wu S, Zhang Y, Dong X, Huang Y, Jin W, Zhu H, Zhao X, Huang C, Xing L, Li L, Ma J, Liu X, Tao R, Ye S, Song Y, Song L, Chen G, Du C, Zhang X, Li B, Wang Y, Yang W, Rishton G, Teng Y, Leng G, Li L, Liu W, Cheng L, Liang Q, Li Z, Zhang X, Zuo Y, Chen W, Li H, Hui MM. A "GC-rich" method for mammalian gene expression: a dominant role of non-coding DNA GC content in regulation of mammalian gene expression. Sci China Life Sci. 2010 Jan;53(1):94-100. doi: 10.1007/s11427-010-0003-x. Epub 2010 Feb 12. PMID: 20596960.

2、Nevis Fregien, Norman Davidson. Activating elements in the promoter region of the chicken β-actin gene, Gene, Volume 48, Issue 1,1986,Pages 1-11,ISSN 0378-1119,https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1119(86)90346-X.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/037811198690346X)

3、Kost T A, Theodorakis N, Hughes S H. The nucleotide sequence of the chick cytoplasmic beta-actin gene. Nucleic Acids Res, 1983, 11: 8287—8301

4、Vinogradov A E. DNA helix: the importance of being GC-rich. Nucleic Acids Res, 2003, 31: 1838—1844

5、Cyranoski D. Giant bird-like dinosaur found: Chinese researchers unearth a surpising find. Nature, published online, 2007, 13 2 Fucheng Z H, Zhonhe Z H, Xing X, et al.

6、A bizarre Jurrassic maniraptoran from China with elongate ribbon-like feathers. Nature, 2008, 455: 1105—1108